Functional Noise Generalize Your Mind

Biosignal Machine Learning

In a previous entrepreneurial project I’ve spend more than a year struggling to build an affordable gesture detection application. The idea was to help amputees get more affordable bionic arms and rehabilitation. I restarted the project from scratch in a fraction of the time by switching the software stack to Julia and BrainFlow.

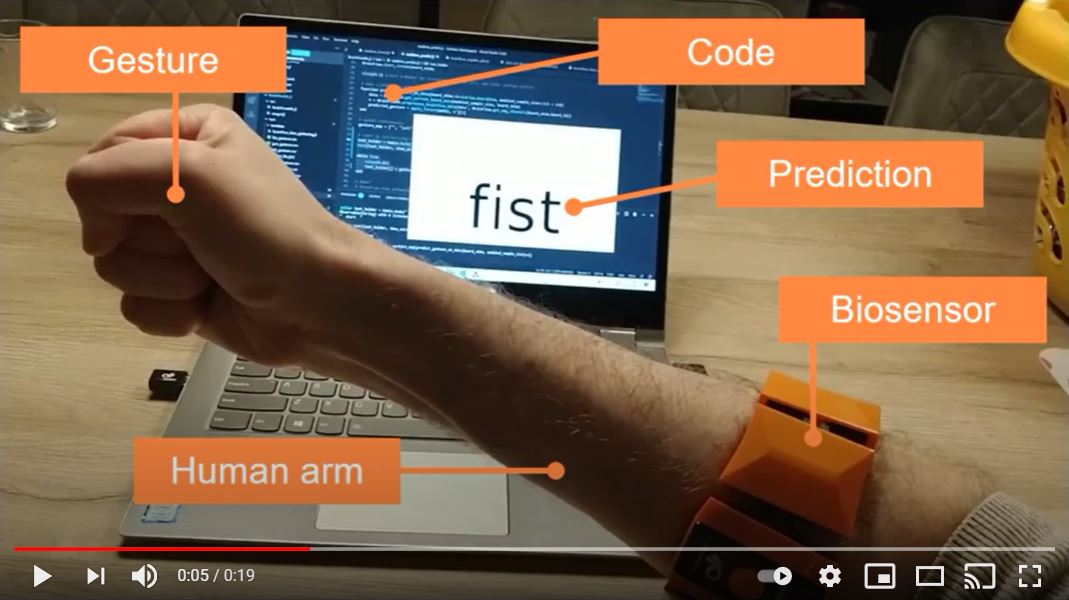

In essence, this side-project is all about using non-conventional body signals to control the physical and digital world. It fascinates me and many others. The easiest thing to control is a video game on your laptop. So that’s what I am aiming for. Here’s what the end result looks like:

I estimate it took me about 40 hours, because I spend a month working on it with only 30-60 minutes per evening. I admit that if you try it yourself, then it may take longer. I already did all the work before in Python, so I didn't have to research anything. I could reuse all my past experience and just copy the work to another implementation.

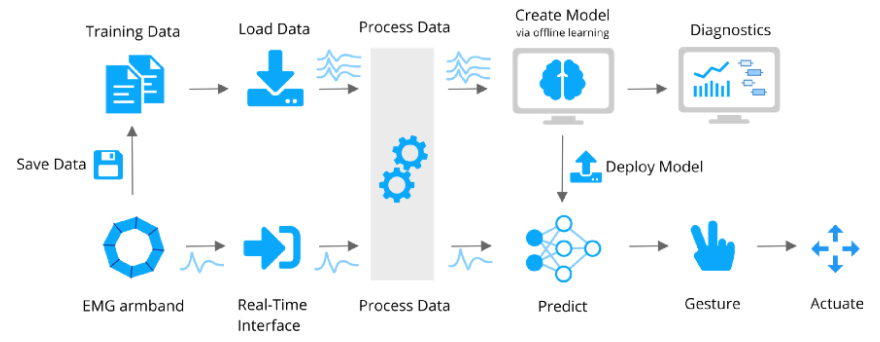

The System

I’ve got a simple overview of the entire system drawn below. I’ll go into the details in the remainder of the article, but the ‘system architecture’ can be divided into two main streams.

The upper stream consists of:

Collect and save data for a bunch of gestures. This is the data required for the machine learning.

Load the data for all gestures in your favorite programming language. I’ll be using Julia for this.

Process the data and split it into training samples.

Fit some nice ML model.

Optionally; do some cool data visualization.

Then later during the realtime prediction:

Acquire a single sample of data.

Process it exactly as during training.

Predict a gesture on the data with your model.

Do something, in this case; visualize some text, or press a button.

Repeat quickly on the next data sample.

(Pro tip: use a high performance language for this second part.)

The Device

Getting a good bio-sensor to measure your EMG (electromyography) muscle signals is actually the hard and expensive part. In the past Thalmic Lab’s Myo armband was popular, but they went away unfortunately. It’s left a bit of a vacuum for DIY EMG hackers like me. Personally I have access to the OYMotion gForce Pro armband, but unfortunately they don’t have good logistics yet outside China, so it’s not super easy to acquire. You can browse BrainFlow’s Get Started guide to see all EEG, EMG and other biosensing devices that are integrated and make a choice yourself.

The code

Before BrainFlow we had to write custom c code to get the armband data, connect it to Python and do all signal processing there. The code of my previous project is here. I replaced the custom c code with BrainFlow and converted all my old Python code into Julia, to see if I could reproduce the results and finally gain enough performance for real time predictions. You can see it all in BrainFlowML.jl

Data Acquisition

Acquiring data from the bio-sensor is a few lines of trivial code with BrainFlow. Make sure your device is on, then just start streaming and get some board data:

using BrainFlow

board_id = BrainFlow.GFORCE_PRO_BOARD

params = BrainFlowInputParams()

board_shim = BrainFlow.BoardShim(board_id, params)

BrainFlow.prepare_session(board_shim)

BrainFlow.start_stream(board_shim)

num_samples = 256

data = BrainFlow.get_current_board_data(num_samples, board_shim)Data Visualization

Before going into all the machine learning, it’s important to eyeball the data. You can do that by capturing some sample data, store it and then plot it. That works alright. But for bio-sensors nothing works quite as magically as just streaming the data live. However, we are talking 8 channels streaming at 600Hz here, no way a simple plotting package can handle that kind of data rate?

I did encounter that problem in the past. Most plotting packages are for static data or simple animations. But no worries, Julia has its own high performance plotting and animation package: Makie.jl.

I’ve described in my realtime biosignal data visualization blog post how to set this up. But the result is amazing! I’ve just got to show you:

Seeing your own biosignals in realtime remain magical to me! With this setup I can now visualize any bio-sensor data. I am busy investigating my own brain waves with other devices, but that’s for another blog post.

I continue to use my own biosignal visualization package to quickly check if the biosensor device is operating decently and the signals are good. If one of the sensors is not touching my skin enough, or the conduction is too low, I see it back in the realtime signals. I can then adjust the device accordingly, or excercise a bit to create some sweat for better conduction ;)

Machine Learning Library

Before diving deeper into the signal processing, let me briefly walk you through my current exploration of Julia machine learning packages.

There is Flux.jl, which is like TensorFlow and PyTorch, except it’s written in pure Julia with relatively little lines of code. It’s absolutely awesome and elegant, but I don’t need deep learning to get the job done, so I won’t use it here. There’s also TensorFlow.jl if you really still want it in Julia.

Then there is MLJ.jl. It’s an automated machine learning package that can incorporate all Julia ML/DL algorithms out there, including Flux. It’s absolutely amazing, but I don’t need it right now.

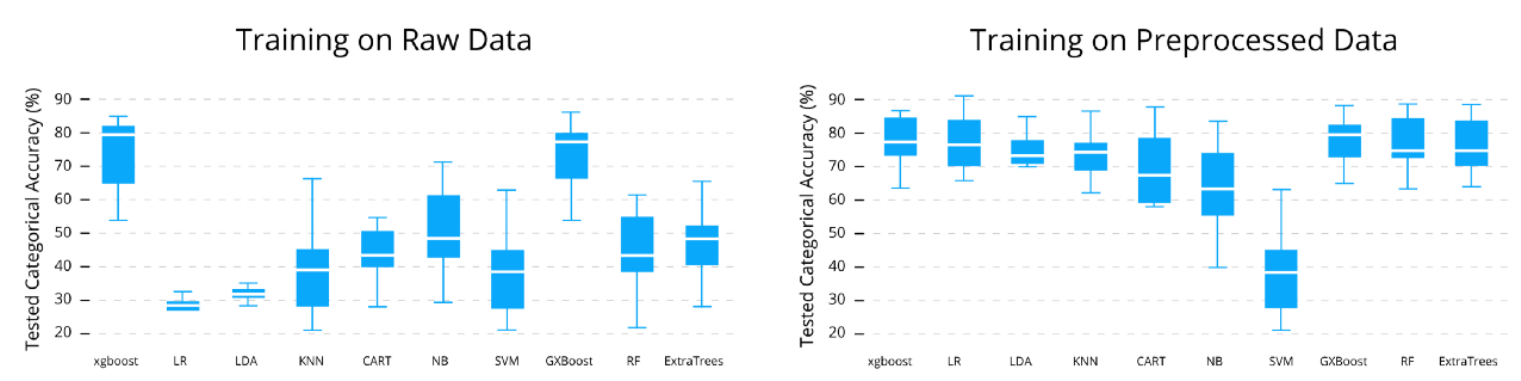

Because in the past we already investigated different algorithms in Python. Turns out with some good preprocessing, most classification algorithms work just fine on this data. I tested this in the past together with a student:

So for now I’ll just choose a simple random forest from DecisionTrees.jl. When I need to compare and tune algorithms to squeeze the last percentages of accuracy, I will definitely go back to MLJ and Flux.

Data Pipeline

Any experienced data engineer can tell you that most AI/ML work is involved in all the data processing, not in the machine learning.

Actually we will have two data pipelines, one for collecting and training the model and one for doing the realtime classification. But they should both use the same signal processing. For that we will use the digital signal processing package DSP.jl. BrainFlow itself also has data filtering functions, so those can also be used.

The OYMotion armband comes with onboard filtering, so the raw signals are pretty good. All I did was detrend the data, in other words remove a constant offset. If you have another device with less electronic filtering and shielding, you may want to apply a bandstop filter around 50 or 60 Hz (depending on your geographic location) and perhaps a bandpass to remove low and high frequency noise.

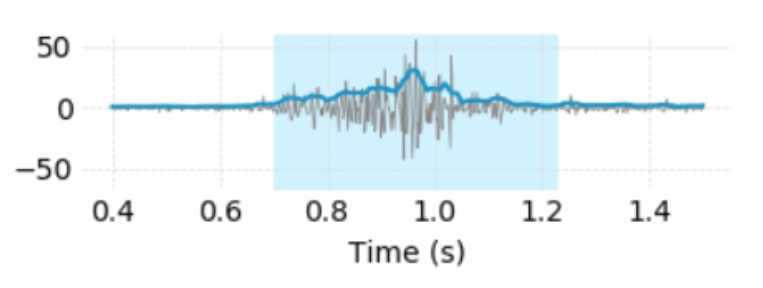

In another blog post I explained how we used a Hilbert transform to capture the envelope function of the EMG signals. That one is available in DSP.jl. I also smoothened it a bit with a savgol filter. Both steps help in detecting the actual gesture and separating it from background noise. There are far more complex strategies available in the literature, but I’ll stick to what I know for now.

Collecting data

I don’t have any database available with data from this bio-sensor, so I have to collect my own. Fortunately we don’t need too much data. I collected 30 seconds of data per gesture; left move, right move, fist and spread. It’s pretty boring, I just make roughly the same gesture multiple times with some variation, sometimes a quick fist, sometimes holding the fist, then a powerful strong fist, then a weaker version.

You can find a simple script to collect data in my BrainFlowML repo called brainflowdatagathering.jl. The main part is the loop that asks you to make some gestures:

so_many_gestures = 4

for n = 1:so_many_gestures

println("Press enter to start recording gesture $(n)")

readline()

data = record_gesture(board_shim)

df = emg_data_to_dataframe(data, board_id)

CSV.write("gesture_$(n)_data.csv", df)

endIt’s pretty straightforward:

record_gesture connects to BrainFlow and shows a progress bar.

then convert the data to a dataframe.

Store the data in a csv file.

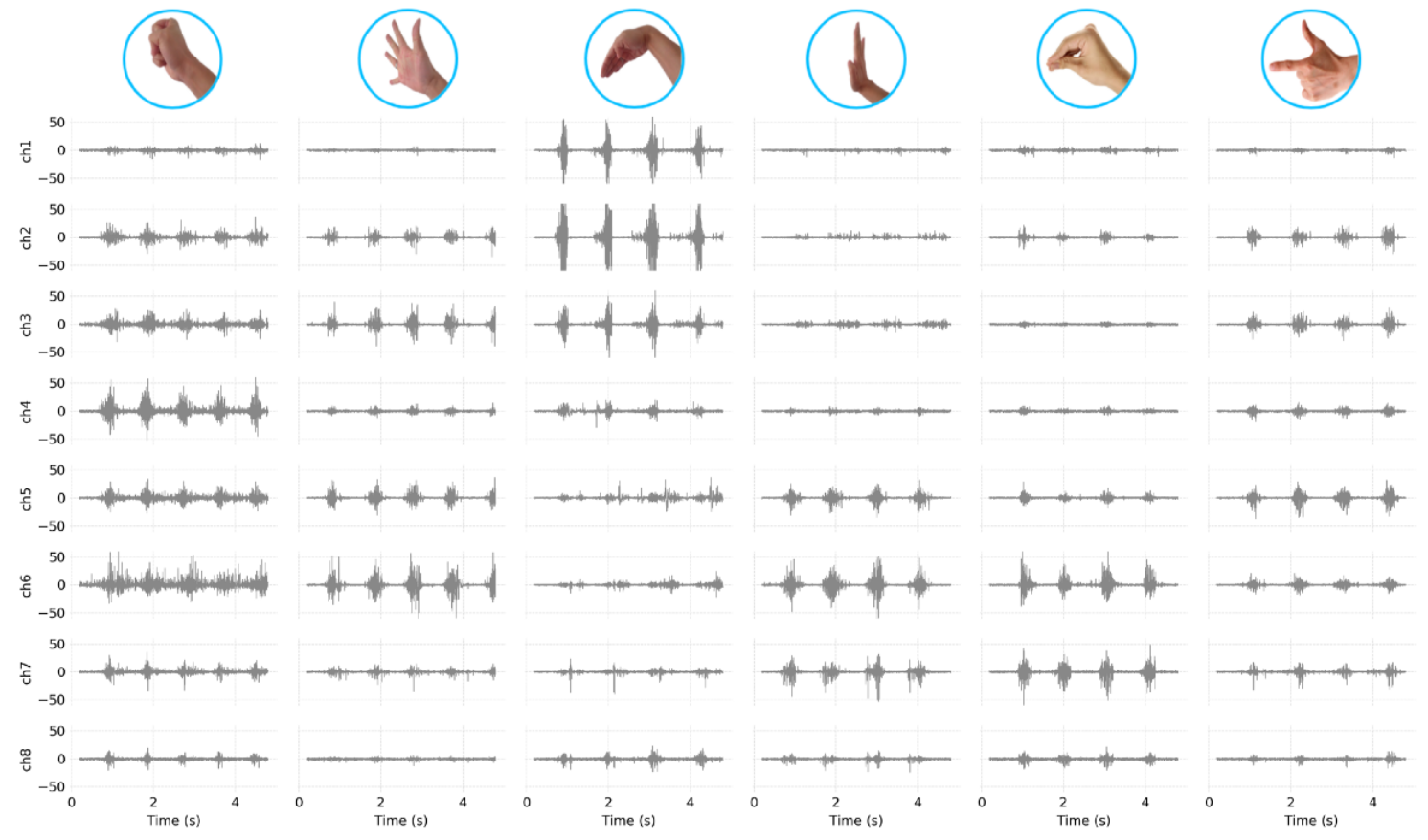

I stored each 30 seconds of data for several gestures in .csv files, you can also find examples in my github repo. Here’s some example plot from 6 different gestures, with the signals per channel in the armband.

The only downside of this simple approach is that the predictions will only work while I keep wearing the device. If I move it or take it off and wear it again the accuracy will drop significantly. For this demonstration it’s fine, but for a real application you’d need something a lot more robust by training on many more samples of data collected under various conditions.

Training the algorithm

Anyway, so I collect data, immediately process it and fit a random forest model on it. During this time I make sure not to change the device position on my arm.

The most complicated part in the training process is labeling the data, to indicate where the gesture starts and where my arm is in resting position. For this I use some empirical threshold on the smooth envelope function. It works decently enough, but is not perfect.

Next to that I have to slice the data into samples that are of equal time length as we will use in the final prediction.

Before passing the data to random forest algorithm, I thus:

Label the data with each corresponding gesture.

Partition the data into a bunch of samples.

Process each sample (just detrend and smoothen).

Make the fit

For more information see my data science article where I already did all these steps in Python. You can also see my example Julia script. In case you like to see some code, here’s how I roughly did it:

using DecisionTree

using BrainFlowML

# my own function to load a bunch of pre-labeled gestures

file_names = ("left_gesture.csv", "right_gesture.csv", "fist_gesture.csv", "spread_gesture.csv")

file_paths = [joinpath(pwd(), name) for name in file_names]

bio_data = BrainFlowML.load_labeled_gestures(file_paths)

# my own function to partition the samples

sample_size = 128

step_size = 20 # gForce sends 30 packages per second with a 600 Hz sample rate, so 600/30 seemed like a good step size

X, y = BrainFlowML.partition_samples(bio_data, sample_size , step_size)

# make sure to process each sample like we will do in the realtime predictions

function smooth_samples!(X)

for s in axes(X, 2), p in axes(X, 3)

slice = X[:, s, p]

smooth_slice = BrainFlowML.smooth_envelope(slice)

X[:, s, p] .= smooth_slice

end

end

smooth_samples!(X)

# stack the channels together

(nsamples, nchannels, npartitions) = size(X)

X_train = transpose(reshape(X, nsamples*nchannels, npartitions))

# train a single forest with some hyperparameters I choose

n_trees = 10

n_subfeatures = size(X_train, 2)

max_depth = 6

partial_sampling = 0.7

model = build_forest(y, X_train, n_subfeatures, n_trees, partial_sampling, max_depth)

predictions = apply_forest(model, X_train)

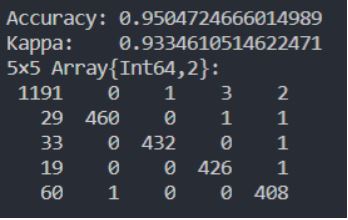

confusion_matrix(y, predictions)As a final check you can look at the accuracy and make a confusion matrix. And instead of a single fit you can also do a cross validation and check the accuracy that way. Both options were available in DecisionTrees.jl. For optimizing the hyperparameters you’d need to move to MLJ.jl, but I found accuracies of more than 85%, which is sufficient for this demo.

The confusion matrix can help you to see if there are any serious misclassifications happening. You can see an example below. The first column is the prediction of ‘no gesture’. You can see these are the most common ones, 1191 times it classifies a ‘no gesture’ correctly, occasionally it classifies a ‘no gesture’ incorrectly as another gesture. For example, 29 times it classifies it as the 1st gesture (a left move of my hand). The ones where the 'no gesture' is predicted too often are not worrisome, they are probably artifacts of my automatic labeling method.

Example confusion matrix printed in the Julia REPL

Finally, I store the trained model on disk so it’s not accidentally lost. I do this with JLD2.jl which can directly save Julia types. There are other methods, but this works fine.

This is the part where I never succeeded in the past, to easily classify gestures in realtime by making predictions with the trained model. But it’s actually quite trivial if you have a high performance language. You can see my example script realtime_predict.jl. All it does is:

Load the trained model.

Connect via BrainFlow.

Make a plot with some text.

Predict gestures in a continuous loop. Update the text based on the prediction.

The result look like this:

I timed the entire data processing pipeline. It took less than 3 milliseconds. Three whole milliseconds to collect the BrainFlow streaming data, smoothing the data and do the classification. Actually most time is lost in the savgol filter because I didn’t try to optimize that piece of code.

This means I have only a 3 millisecond delay. Some people commented that if you watch the video closely, you can see it detects the gestures before my own hand moves! I could never expect such performance with handwritten Python code.

Ruling the world

Now you’ve seen how to detect gestures with your own biosignals. Next you can control any physical or digital object, like a video game as I’ve shown in the top of the blog. That one is trivial, just make the code press a button instead of printing text. Controlling a bionic arm (my original ambition) is a bit more involved, but these sensing concepts are the same. The sky is the limit! What would you build with this technology?