Functional Noise Generalize Your Mind

Organizational Refactoring

Most institutions are deeply inefficient, they barely act according to their stated purpose, surviving merely because competitors are even less efficient or non-existent. Or so they say. Thankfully I am an optimist who accepts this knowledge as an opportunity to improve matters. So let's go do that! I see institutions as dynamic forms of information systems, much like evolving code bases. Since software engineering has learned how to refactor large legacy codebases while keeping their function intact, so too can we learn to refactor large human organizations and improve their performance.

I’ll start this post about how people organize themselves, or rather how they separate themselves into local optima. Then I’ll share some mental tools to refactor towards a global optimum and finalize with my own lessons learned in organization refactoring.

Social emulsion

Humans are pretty good at large scale coordination, at least better than the other species on the planet. However, we still have a tendency to segregate into energetically favorable subgroups. It’s almost like we are an emulsion that will separate automatically unless some agent keeps it mixed and coordinated. In an organization that does requires multiple tasks to be done, some people prefer task A and some people prefer task B. The people who prefer task A really like talking to each other about A and begin to seek out the other A people, and voila, separation begins.

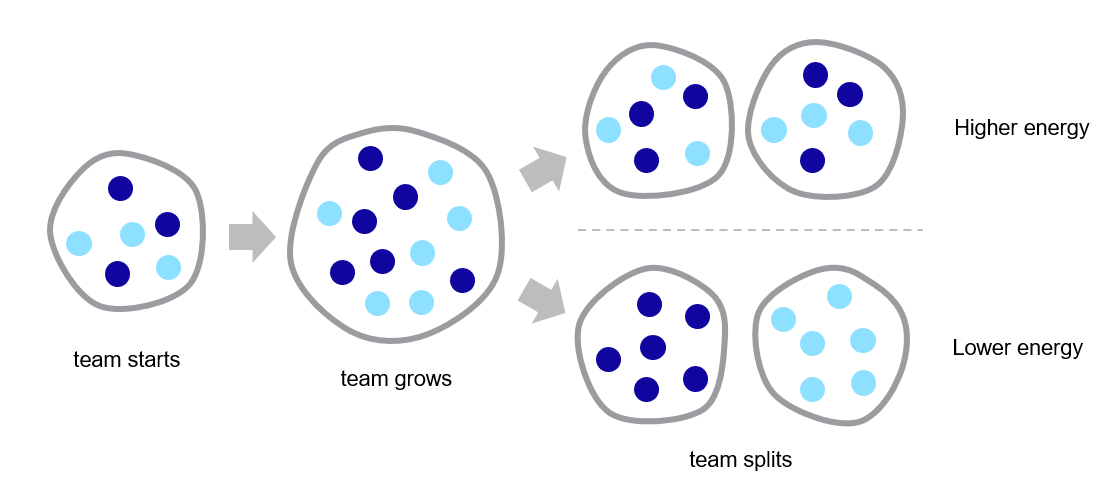

Let’s imagine growing a new company or team. At first when we start, we need people with multiple competences, we need both people who can build products and people who can sell them. So we are forced to work together. When the team is successful it will grow and we can no longer collaborate with everyone at once. The team will split, either naturally or via management decree. How do we split? The easiest split is along a line where people work together effortlessly. So we create a marketing department, a development department, a research department. Even if early management foresaw this problem and splits with end-to-end development effectiveness in mind, at some point the departments become big and internal segregation into subcultures begins.

This simple model assumes some kind of interpersonal friction exists, which is reduced in the presence of shared interest among people. Another type of friction comes from using different tools and languages, which make it harder to collaborate. Why are different tools being used? Either people are doing different tasks, solving different problems, which really need different tools. Or people start out independent from one another and accidentally use different tools and languages. Note that I am not advocating for tool uniformity. You should use the best tool for the job. But if separate people use separate tools and this makes the job harder, than we have to admit our mistake.

The best results are achieved when we have diversity in ideas, while having a common goal and the least amount of cognitive load from using different tools. We want the brainpower to focus on what matters in business: creating valuable products and services for our customers.

What’s the big problem?

You might still ask: so what? So what if people organize into separate clusters and throw work over the fence? Work in each cluster will benefit from highly specialized people who can do the job very efficiently. Unfortunately, this is not guaranteed to improve the overall performance. You may be falling for the false believe that optimizing the parts of a system will also optimize the whole. What happens instead is that you will create local optima and one of them is going to be the primary bottleneck. This is nicely described by the Theory of Constraints (TOC).

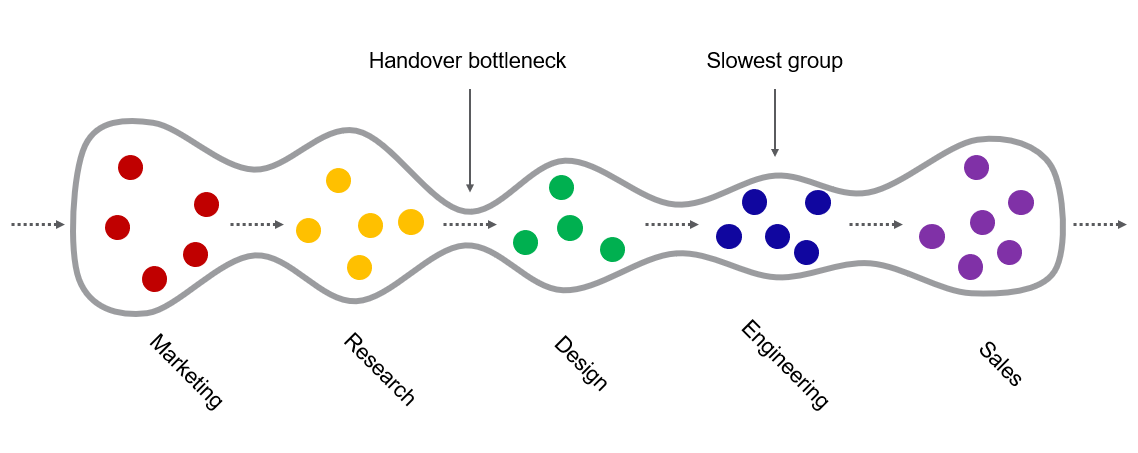

Let’s say a succesful product moves from an idea in marketing to research to design to engineering to sales. It doesn’t matter if you can imagine multiple paths, the theory works fine on complex graphs as well. Each group/team/cluster/culture/department is uniform and highly optimized for their specific task. However, one group will be the limiting factor in the flow due to some reason. This is the toy model described in Theory of Constraints.

Actually, what I believe is missing from the Theory of Constraints, is that the handover from one group to another is typically the bottleneck in knowledge work. People do not understand each other, so information is lost in translation and frustration. Therefore you’ll find a bottleneck somewhere, either because one group is the slowest in the flow, or more likely because one handover is the least efficient.

Possible solutions

Let’s say you find yourself in an organization that’s suboptimal. We have two options available to us:

either accept the current structure, find and elevate the main constraint. Then repeat.

or refactor the organizational structure for optimal flow (see for example Team Topologies).

The first option seems easier as it can be done in small increments. Though there are long-range effects, since you may have to convince people in the surrounding teams to become less efficient (just read the TOC blog, alright). I am very curious if the second option, organizational refactoring, can also be done in small increments, rather than big re-organizations as is typically attempted. Let’s have a look at that.

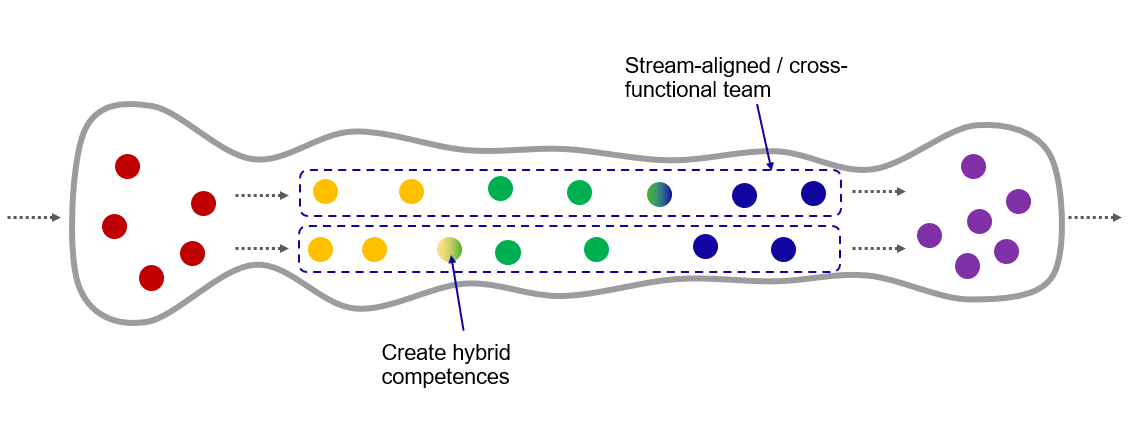

Personally I believe refactoring the organization is best for finding the global optimum. Ideally you have cross-functional teams that can take ideas as far as possible, from inception all the way to the customer. But you can start by making cross-functional teams at the primary handover bottleneck. Such a team needs to have people from both competences and should have the best tools for the job. The team can then locally optimize again, but now it has the capabilities to resolve the bottleneck internally.

I definitely advise to read the book Team Topologies where such teams are called ‘stream-aligned teams’. In other management frameworks, such teams are called ‘cross-functional teams’ or ‘full feature teams’ or otherwise. It doesn’t matter how you call them, what matters is to optimize the flow, which is ideally done locally within a team if possible. When you begin refactoring towards the ideal team topology, it’s best to start at a handover bottleneck to see immediate results.

An interesting people aspect of such a team is that members are free to learn the competencies they are best at. Some people prefer to learn multiple competencies, which results in ‘hybrid’ skillsets and provides a new kind of personal growth path. Others may learn adjacent competencies shallowly, which will result in so called T-shaped individuals; people with a primary competence, but with enough external expertise to smoothen the knowledge transfer between individuals. Both are excellent improvements if they elevate the constraint, improve flow and add future flexibility.

Research and development refactor

Personally I am most interested in moving ideas from research to production, primarily in the field of numerical computing. This is my day job, so consider the following a case study based on my on-the-grounds experience.

The general issue is that the time from research to production is loooong, often spanning multiple years per project, and growing longer over time. Some common smaller issues we see arising in many of our projects:

Unreproducible, unexplainable scripts or notebooks in research

Effort to translate from one technology to another

Difficulty optimizing the idea for direct product integration

One typical constraint problem we observed is the following. The researchers quickly write a prototype, management wants it turned into a product, the software engineers then spend ages deciphering the prototype and converting it for the production systems. Because the researchers are not the bottleneck they continue tinkering with the prototype and bothering the software engineers with new insights, which further reduces the overall efficiency. Meanwhile other researchers find new prototypes and hand them over to these software engineering teams. This can result in a never ending cycle of downwards productivity.

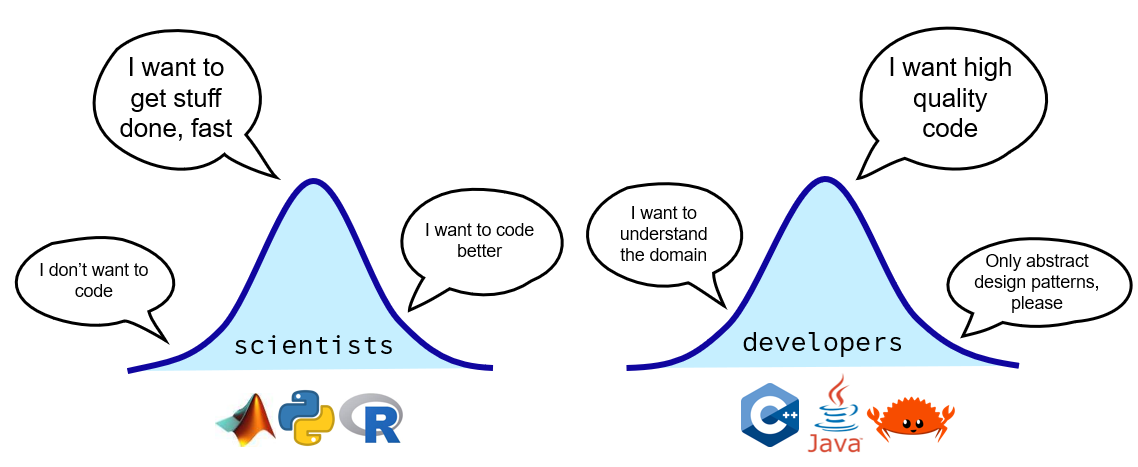

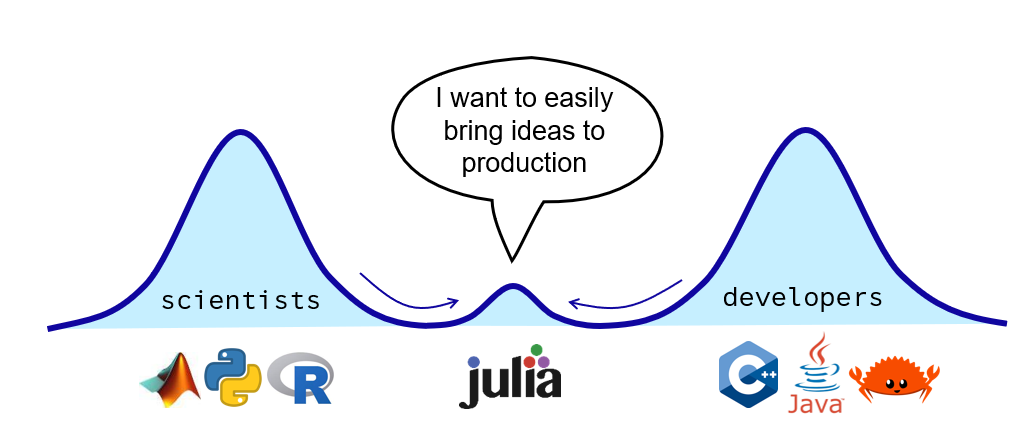

While many improvements in this scenario are needed and possible, we decided to focus on one main area which attracted lots of interest from the engineers and engineering managers: the technology differences. For many years it was taken for granted that we need different tools in the separate phases between research and product development. For quick research and exploration you use an easy to use programming language, for example Python. For high performance, reliable, scalable production environments, you use a language like C++, sacrificing ease-of-use in favor of these important utilities. This two language problem immediately creates a bottleneck in handing over ideas smoothly for development.

The “two language problem” was globally accepted for several decades. Until one day it was challenged by the Julia language, a programming language that promises both speed and ease of use. Together with several allies I went on a mission to adopt this new technology at work, and remove the bottleneck.

While we had initial success and attention, we quickly stumbled into resistance from the existing groups of researchers/scientists and developers. Over time I have named this the “two culture problem”. For a while I didn’t see the cultures consciously, which limited our success. I was too focused on the technological problem itself. However, as you may notice, most of the blog so far has been about this organizational challenge, which I learned the hard way.

I will refer to the two cultures as “scientists” versus “developers”. However, the “scientists” group generalizes to anyone who codes quick and dirty to explore, such as domain experts, data analysts and others like that. I do hope everyone is doing their exploration somewhat scientifically, so the generalization should makes sense. The benefit of these two names is that I can call the middle ground “scientific developers”, which is the kind of people I have in mind to form the bridge between these two cultures.

Rise of the Scientific Developer

People who walk between cultures feel the friction, yet see both the problems and the opportunities. Often an individual can become immensely valuable by learning the skills that people stuck in their cultural ivory tower are unwilling to pick up. (Remember: they are valuable since they can single-handedly elevate the constraint.) I’ve also been inspired by the DevOps movement which tries to address the aspects that help move products faster from development to operations. To better move ideas from science to development, I will call these people “scientific developers”, perhaps SciDev as a field and SciDevOps for those who can go all the way.

Turns out we are trying to engineer a new group with new tools right there in the gap. The people on the outer edges of the other groups are attracted by this opportunity and are the prime candidates as members of this group of scientific developers. This is the starting point for our organizational refactoring.

The Julia language is one perfect tool for scientific developers, designed for their needs, though not necessarily available to use in their current organization which may force upon them the tools of the dominant cultures. I have spoken with many who see this bottleneck, but are frustrated that they are not allowed to solve it. This is a good sign! There is a desire for bottom-up change.

Note that Julia can never be the only tool. A scientific developer must be proficient in the scientific principles and relevant domain knowledge next to the craftmanship of software engineering. For a scientist this involves learning many professional software engineering techniques such as version control (GIT), test-driven development, distributing reproducible environments and packages, documenting your code, proper interface design and much more. The software engineers will have to learn all the specific domain knowledge from the ‘scientists’.

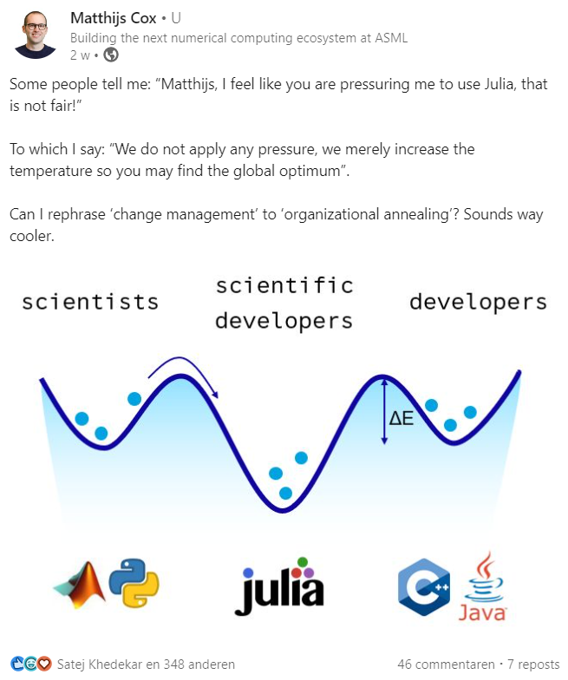

Overcoming Resistance

When trying to move a system out of a local optimum towards a more global optimum, you will encounter an energy barrier. In human organizations this means an active resistance to change. This resistance comes in many forms. People will not believe your solution is the optimum and ignore your refactoring initiative, or actively try to thwart it. Some don't want to leave the comfort of their local optimum. Some people will believe in the solution, but do not have the power to overcome the energy barrier, often they have no slack to take a temporary hit in their efficiency, maybe out of fear for losing a promotion or being fired.

I’ve succesfully joked on LinkedIn that we should ‘anneal’ the organization, a numerical optimization technique to find the global optimum, or actually a term derived from metallurgy that involves heating and controlled cooling to change the microstructure of a material. It's a funny view, but I do fear in reality you need some more active work to pursuade people to cross the energy barrier.

Some ways to overcome the resistance are:

First find the motivated individuals, the high energy particles so to speak

Having higher management support helps

Teaching people the right skills lowers the threshold

Setting up easy infrastructure ahead of time

Starting with smaller examples you can later to refer to

New projects can be an easier place to start, instead of refactoring old legacy code bases. It helps to decouple the organizational refactoring from the codebase refactoring, but it's not always possible.

Failure modes

You can learn from our failures and complexities. I can identify at least a few:

Spend all your time arguing

Rather than merging, spawn a 3rd culture

Refactoring across a political power line

Talking too much

Sometimes people think that persuasion involves only talking. While you need to have a captivating story, the best way your adversaries can derail your refactoring is to lure you into endless arguments. (Beware false allies who only talk.) You can learn from good criticism, but if you have proof of the constraint, you should spend most time finding allies and running experiments, for example by starting a new team with your allies. The best arguments are real proof points.

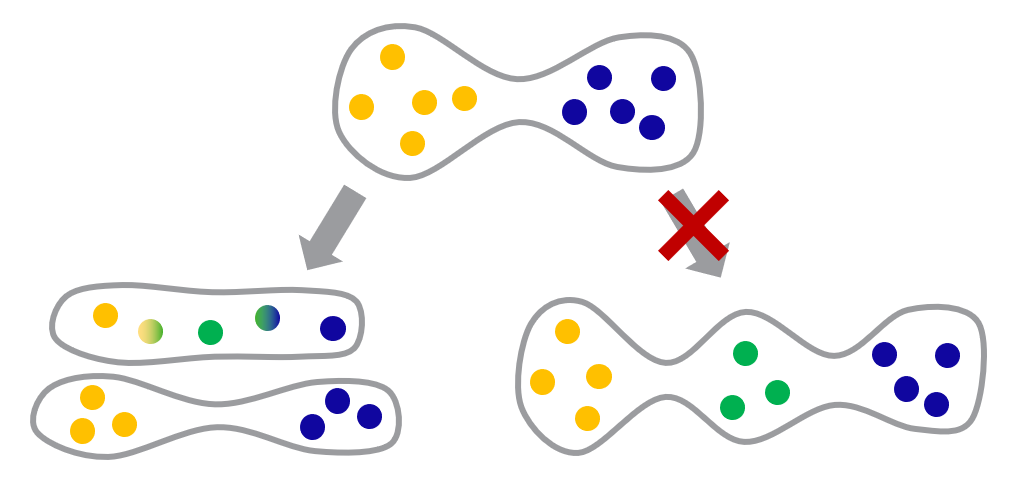

Spawn another culture

The purpose of our refactoring is to remove a bottleneck and replace it with a more optimal end-to-end team. An acceptable intermediate state consists of some teams in the old configuration and some in the new experimental configuration. This allows gradual refactoring and is actually great for comparison. The state you do not want to end up in, is by introducing a 3rd intermediate team, where you risk similar handover bottlenecks and a longer process to move from start to end. I’ve seen the latter configuration proposed several times by managers, as it seems easier due to less internal resistance in the original teams, but you are only creating more local optima.

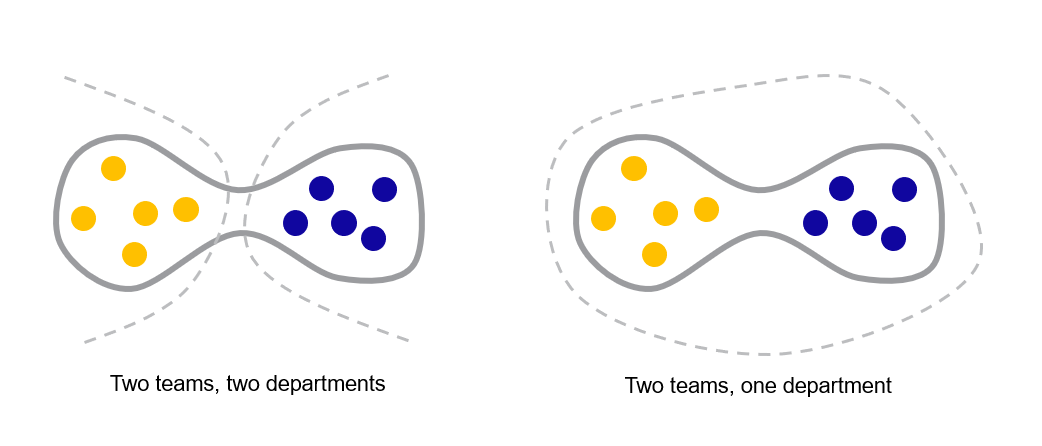

Power divides

So you might have identified two teams (or some other unit in the flow) that you want to refactor into one. Now assuming you are a naïve junior organizational architect like me, you may be unaware of the greater power structures at play. Basically I got lucky and the research and development teams existed in the same department where I work, so I got full support to start a new experimental team to do both at once. This worked out wonderfully.

However, others got less lucky, where the teams worked in separate departments. Each department was mostly homogenous with multiple teams performing a single task in the flow. This can be tough. It may be the separate department managers (or whoever is in control) are allied and willing to cooperate. That gives you a chance. It may also be that the bottleneck is there on purpose as a defense mechanism against political competition, or the local optima are serving the existing power base in some other manner. That’s bad luck. Your refactoring needs support from a higher level, which you may not have at the moment. Even if you are the higher manager, or have higher management support, the mid-level managers may simply be too powerful to change.

In general, you’ll need great persuasion skills and cooperative assistance (either a big alliance, or management support) to succeed. This can be a tough pill to swallow for engineers who like refactoring information systems for efficiency reasons. However, I remain optimistic about organizational refactoring, since technological leaders seem more willing to set aside their ego and look at the system objectively.

Conclusion

This turned into a much longer blog post than I imagined, but I enjoyed summarizing my thoughts on the matter. I fear the engineers in my audience will find this story rather fluffy. I know my past self would also be surprised that I am involved with such seemingly irrational, non-scientific, business management, magical thinking. Perhaps I crossed fully into meta-rationality now, which is a possible evolved state of a rational thinker.

I do hope more engineering leaders join me in organizational refactoring. I can't say the work is always enjoyable, but it's important. Those who deeply understand Conway's law, know it is necessary for succesful technological designs. To keep you inspired, I will end this post similar to my other magical thinking piece: refactoring organizations is just like refactoring code, only a little less rigorous and a lot more nebulous.